In December 2000, Lionel Messi was 13 years old and on the brink of slipping through Barcelona’s fingers. The club wanted to sign him, but nothing was official. Paperwork stalled. Approvals lagged. His family, facing uncertainty over money, medical treatment and residency, was preparing to return to Argentina.

So Barcelona’s sporting director, Carles Rexach, didn’t wait.

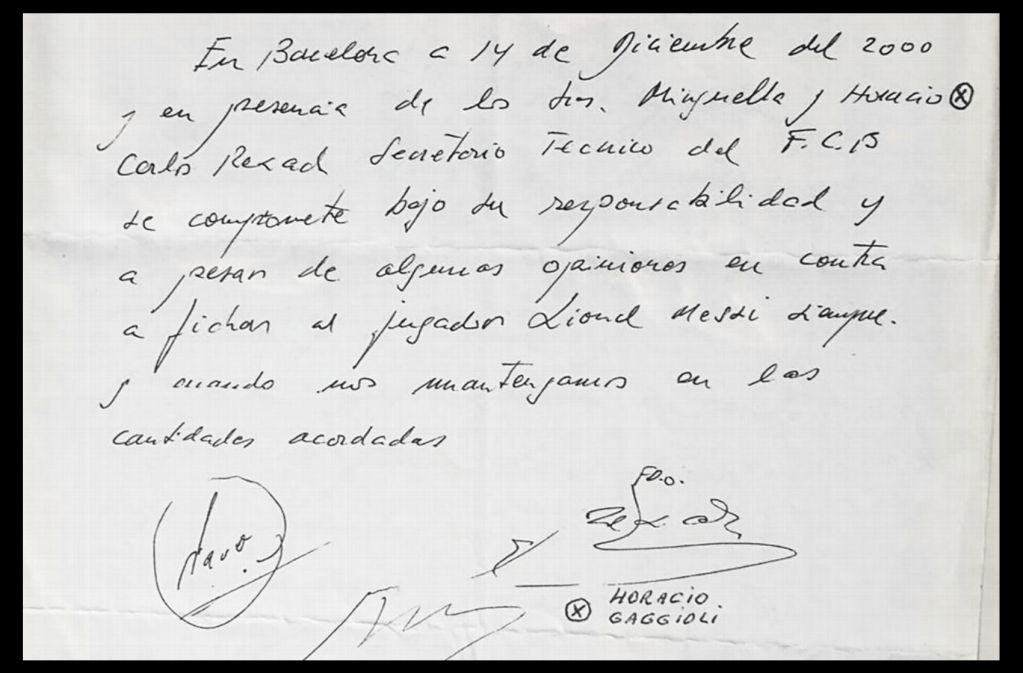

At a restaurant near the club’s offices, he took a napkin and wrote a simple but binding agreement. In Barcelona, on 14 December 2000, in the presence of witnesses, FC Barcelona agreed to sign the player Lionel Messi. Rexach signed it. Others witnessed it. It was legally sufficient to count as a commitment. The formal contract would come later, but the napkin was the moment that mattered.

That napkin still exists. It has been authenticated, displayed and auctioned. One of the greatest footballers in history was first secured on restaurant stationery. Football heritage, it turns out, can be gloriously chaotic.

What delayed Barcelona was not a failure of imagination, but the ordinary drag of bureaucracy. Messi had a growth hormone deficiency; treatment was costly and required board-level approval. He was a foreign minor, which meant visas, guardianship arrangements and federation rules. Internally, the club was divided: some saw a prodigy, others saw risk piled on risk at a financially unstable moment. Meanwhile, Messi’s family needed certainty, not reassurance that processes were under way.

Rexach saw something the system could not yet formalise. He also understood that delay was itself a decision, and likely the wrong one.

This is how leadership often reveals itself: not in flawless strategy documents, but in moments when instinct collides with procedure. Modern organisations like to believe that good decisions emerge from exhaustive process. Sometimes they do. But process is designed to manage known risks, not fleeting opportunities. It struggles with the fragile, the exceptional, the not-yet-provable.

Leaders who act early accept exposure. If they are wrong, they own the failure. Bureaucracy exists partly to spread that risk so thinly that no one is blamed, and nothing decisive happens. Acting on intuition concentrates responsibility on one person, which is why it feels dangerous and why so many avoid it.

The difference between recklessness and insight is not speed but judgement. Rexach was not ignorant of the risks. He simply believed the greater danger lay in waiting. He understood that some chances do not survive committee review.

In hindsight, these moments are tidied up. Contracts are formalised. Policies catch up. The risk is retroactively rebranded as foresight. What disappears is how uncertain the outcome felt at the time, and how easily the decision-maker could have been condemned rather than celebrated.

Not every napkin leads to Lionel Messi. Many instincts fail. But organisations that never allow room for such leaps quietly choose stagnation over possibility. They confuse caution with responsibility and paperwork with wisdom.

Sometimes leadership means knowing when the rules are protecting judgement, and when they are merely postponing it. Sometimes the most responsible act is to sign first and file later.

History will decide whether that was vision or folly. Bureaucracy never can.

Leave a comment